Creating an entire career that had not truly existed before is one of the qualities that makes Farida A. Wiley a woman of impact. Miss Wiley was born on a horse farm in Sidney, Ohio. As a young girl, she took an intense interest in the birdlife around her, even sending reports on the nesting birds of her childhood neighborhood to the U.S. Biological Survey when she was only 12 years old.

After ending her formal education at the high school level, she arrived in New York in 1919 to teach botany part time to blind students at the Museum of Natural History. She was able to obtain such a position even though she had no college education through the influence of her brother-in-law Clyde Fisher, who worked for the Museum and later founded the Hayden Planetarium. But she far exceeded anyone’s expectations as a self-taught naturalist. Although a similar career now would require academic training, Miss Wiley taught not only at the American Museum but over many years, at Pennsylvania State College, the Audubon Camp in Maine, and a New York University branch on Long Island as well.

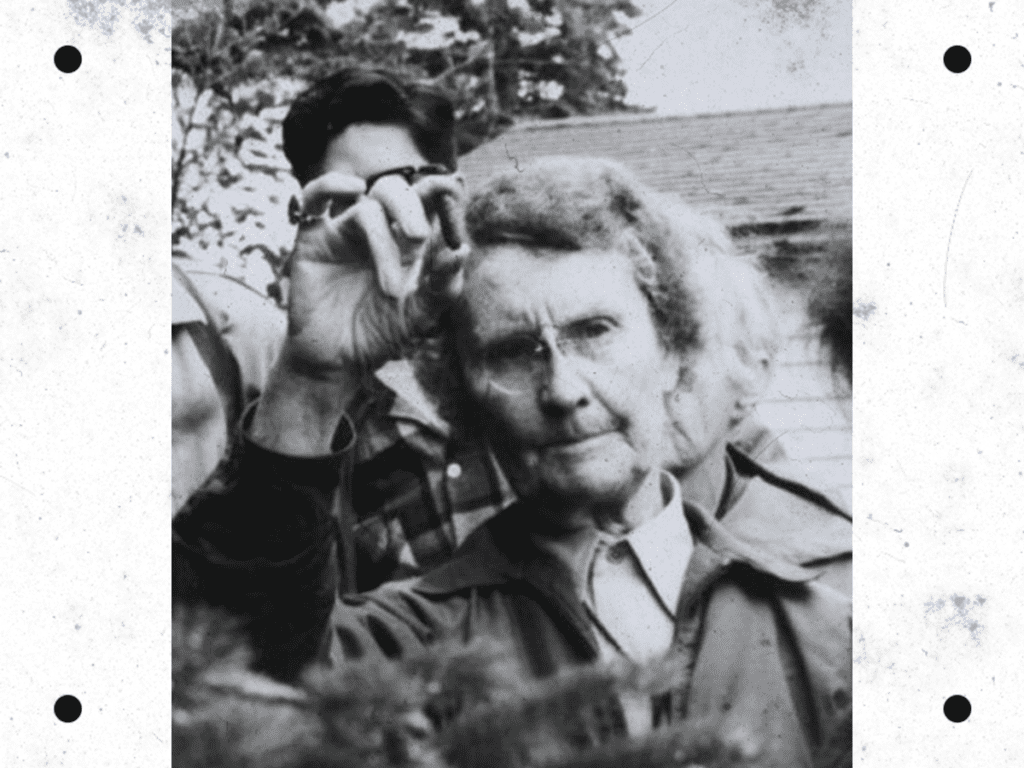

However, it was as a guide to generations of Central Park bird watchers that Miss Wiley became so well-known that both The Washington Post and The New York Times ran multiple-page obituaries when she died at the age of 99, having retired from her tours at the age of 94. Although Farida Wiley had served for 60 years as a full-time staff member of the Museum revealing the wonders of nature to the students in her classes, she was probably best known as the person starting in 1938, who led many thousands of people on early-morning hikes through The Bramble, a section of Central Park ideally located for birders. Toting field glasses and bird manuals, the people would listen to her lecture on the scores of migratory birds using Central Park as a resting place.

Miss Wiley was considered all-knowing about birds, plants, and trees. She also was a renowned author in her field, counting among her books a definitive work on ”The Ferns of the Northeastern United States,” first published in 1936 and having written or edited a total of six books. In 1953, the Museum of Natural History in New York awarded her its Silver Medal for ”over 50 years as a distinguished naturalist and teacher.”

”We go out, rain or shine,” was her motto, whether she had scores or just three or four bird watchers on her 7:30 and 9:30 A.M. tours of the park. She walked at a gallop even as a woman in her eighties and taught people to make a connection with the world –to look up and out- beyond themselves. She led an extraordinary life, was a woman of uncommon character and was said to “have radiated honesty… with no phoniness, no subterfuge, no using of people. She was herself. You came away thinking: ‘Now there’s a person.’” She was truly a trailblazer. (Information excerpted from The New York Times and The Washington Post)